Commitment contracts: a personal example

Last updated on 23rd July 2012

(This post is downloadable as a Word doc or a PDF file).

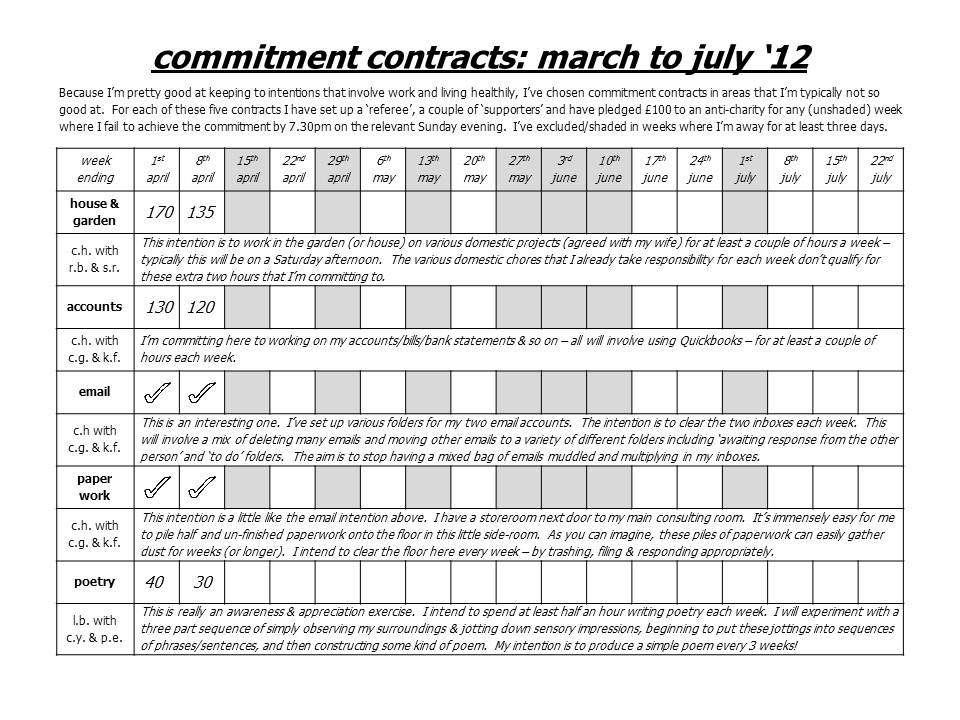

I've already written a couple of posts about commitment contracts - "Commitment contracts: another good way of helping us reach our goals" and "Orientation, practicalities & use as therapeutic tools". I'd like to illustrate some points about setting up these contracts with a personal example. As Ian Ayres puts it in "Carrots and sticks" (p.xx) " ... we know that commitment contracts are not a panacea. But I hope to convince you that by attending to their structure, we can better stick to our commitments. Small differences in detail matter. It is foolhardy to enter into any old commitment without thinking about close to a dozen different dimensions of design."

As I pointed out in yesterday's post, a key first issue is in choosing what to commit to in the first place. There's a fair amount of work involved in setting up a good commitment contract. To make the effort worthwhile it's important that a.) You genuinely want to achieve the goal you're committing to. In other words, in the end, you're doing it because it is truly something that feels right to you to aim for. b.) The goal is challenging but achievable. It's not worth the work of setting up these contracts for goals that are too easy, and it's certainly not worth the work for goals that are likely to be unachievable. So for me with the five commitments I make below, these are all things I would genuinely like to do. I'm very good at achieving work-related and healthy lifestyle-related goals, but this more "administrative" cluster of tasks I have half-heartedly aimed for and failed to achieve on a whole series of occasions in the past.

A second important issue is that the goals are concrete and specific. "Exercising more" is unlikely to be precise enough. "Jogging for 20 minutes three times each week" is a much clearer target. Hence my specification of times in the goals below. Thirdly it's likely to be important who you ask to act as "referee" - as the person who confirms whether or not they agree that you've reached the (weekly) goals you're aiming for. This may well end up as a compromise between convenience and caution. For some of my goals I've asked my wife to act as referee. It's very convenient. She's the person I live with and she can easily, week by week, check whether the storeroom floor really is clear of papers and my email inbox really is empty. The caution is that it may be too easy with family members & close friends to let boundaries get sloppy. "Come on, you know I've had a very busy week. Give me a break, the storeroom floor is mostly clear!". We really do need tough love here. Our inner Mr Spock needs to ally with and orientate our referee (and our supporters) against a possible future emergence of our inner Homer Simpson!

What about choosing "supporters". These are people who you're going to keep informed about your progress. Lovely if they care about you and want to encourage you. It may also be sensible to choose supporters who have already achieved the kinds of goals you're aiming for. We affect each other - see the post "Be the change you want to see in the world". So L.B. and C.Y., who have agreed to act as "referee" and "supporter" respectively for the poetry intention, both write poetry pretty regularly. R.B and S.R., garden/house project supporters, are friends of my wife's and myself and are very involved in gardens & nature. Actually "going public" over one's intentions can easily be as strong or a stronger motivator than putting money at risk. For example, going public on this website about my intentions and stating that I will blog monthly on how I've been doing should act as an additional powerful make-it-happen motivator for me.

What about putting money at risk? Or setting up potential rewards? As Ian Ayres points out in his book "Carrots and sticks", it's pretty clear from a whole series of research studies that we're typically more driven to avoid losses than we are to make equivalent gains. And the money I put at risk is not about some kind of "incentive" scheme. The amount chosen is meant to really motivate me not to fail, not just to be a "slap-on-the-wrist" penalty I am fairly happy to occasionally pay. The penalty is meant to be large enough to be a powerful disincentive to our inner Homer Simpson when he starts to emerge. Clearly we don't want to choose such a large amount that it would damage us badly if we lost it, but we want the size of the penalty to get our attention. This is going to vary a lot from person to person. Because of the way that I work, I'm relatively "poor" for a doctor here in the UK. I am however very busy. I want the potential penalty to "wake me up". My gut feel is that £100 gets my attention better than the £50 per commitment per week that I originally began to choose. It's a paradox that we may well find that a large penalty is such a strong disincentive to stray, that we end up paying less overall than if we'd chosen smaller penalties that we might be more inclined to sometimes simply accept. If parking illegally automatically led to one's car being blown up, we would be likely to approach the risk of getting a parking ticket with more caution!

However there are dangers too in choosing excessively large penalties. These include the potential for self-damage (for example losing large amounts of money), the possibility of being put off trying commitment contracts in the first place, and - fascinatingly - the possibility of overcompensation after the contract has ended. So there's some evidence (see Ayres's book again) that change achieved under the pressure of excessively draconian penalties may be less persistent (once the potential penalties have lifted) than change achieved under somewhat less duress. This makes the choice of penalty size an interesting issue. We don't want it to be so small that we're too easily prepared to let the contract slip and pay the minor costs involved. But at the same time, we don't want the penalty to be so large that we're put off even starting - or find that as soon as the contract terminates we breathe a huge sigh of relief and rapidly return to our pre-contract behaviours. This is where maintenance contracts, after the initial goals are achieved, are so relevant and - sadly - so often underused. Additionally it's probably important to link back repeatedly to why one has set up the commitment contract in the first place. We want the key motivation to be autonomous - because the goal genuinely feels right to us. Concern about financial penalties and other people's reactions may give additional motivation, but we're only at risk of these because we're using them to add further fuel to our central motivation which comes from our own personal values & priorities.

Rewards for achieving commitments are an interesting area. They tend not to be as powerful but, in many organizational situations, they may just be socially hugely more acceptable than penalties. As individuals though we can go straight for the penalty contract strong medicine for ourselves even if it can taste fairly yucky ... or maybe especially because it can taste fairly yucky. Fascinatingly, tangible rewards may be more motivating than their money equivalents. I'm putting £100 per commitment per week at risk. At worst I could lose £500 in a single week. However as a reward for achieving a full house of all five commitments in a week, I'm going to let myself buy a music CD. It's a bit out of balance when considering the potential penalties I've set up. However the tangible nature of a music CD is likely to make it more memorable than if I simply gave myself a £10 reward for a successful week of commitments.

It's not rocket science to realise that penalties have to be believed in if they're going to be helpful. This is where a website like http://www.stickk.com/ can come into its own by taking your credit card details at the same time as you set up your commitment contract. I've decided to go through with my series of five commitments without using a specialist site. I have however written out five cheques for £100 each and sent them to the relevant referees/supporters with stamped addressed envelopes for my anti-charities and a strong request that if I miss a commitment any week (without an agreed get out clause) they will remember the importance of tough love and send the cheque off to the charity. "Anti-charities" are an idea that I picked up from Ian Ayre's "Carrots and sticks" and http://www.stickk.com/. They are chosen to add further energy to trying to avoid having to pay financial penalties. Knowing the money is going to a "bad" cause rather than a "good" one removes any self-justification one might attempt if one incurs penalties for not reaching chosen commitments. stickK.com is open-handed here. You can choose any of the main political parties or main football teams as your anti-charity. You can choose pro-abortion or anti-abortion charities, pro-climate change action or anti-climate change action charities, pro-blood sports or anti-blood sports charities, and so on. Just select your own poison, your own cause that you would much prefer not to support.

What else to say? Choose commitments that stretch you, but be realistic. The time to do them is going to have to come from somewhere. The five commitment contracts I've set up above are ambitious, but then I'm typically good at achieving goals that I set myself. It's like setting yourself a target running time for a race. You want to challenge yourself but be realistic about how fit you are to start with. Be realistic about the time you have available and how effective you typically are at these kinds of self-control challenges. The good news is that there are so very many great reasons for getting better at reaching our goals. See for example the post "Would you like to be 14 years younger - it's largely a matter of choice!" or my much recommended "Self-control, conscientiousness, grit, emotion-regulation, willpower - whatever word you use, it's sure important to have it". Self-control is largely a matter of being able to achieve important self-chosen longer term goals despite the many potential distractions we come across along the way. Of course it's crucially important to be able to smell the flowers as well. However self-control and savouring can be friends not opponents, and commitment contracts are another potentially helpful tool in this exploration of making the life we want. As the Hasidic rabbi, Susya, said "When I get to heaven, God will not ask 'Why were you not Moses?' He will ask 'Why were you not Susya? Why did you not become what only you could become?'"

If you'd like to hear how these contracts went, see the fourth post in this series - "Commitment contracts: they really can help us achieve personally difficult goals" .