Routine Outcome Monitoring can really help therapists clarify where they need to try harder

Last updated on 23rd April 2015

I recently wrote a couple of blog posts - "Psychotherapy (and psychotherapist) outcomes are good but largely stagnant" and "Fascinatingly, therapists themselves vary considerably in their effectiveness". In the second of these posts I commented "A paper published just last month (Green, Barkham et al. 2014) found that the 25% least helpful therapists in their study produced effect sizes of about 0.2, while the most helpful 25% produced effect sizes of more than 0.9 (with the most effective therapist getting considerably better results than even this impressive effect size) ... Imagine the huge improvement in service effectiveness – with major resulting reductions in suffering, disability and death – if poor therapists could learn to be as helpful for their clients as excellent therapists are." One potentially immensely helpful resource for us as therapists would be to more routinely get clear feedback on what results we are achieving - seeing where we're being a more effective therapist and where we're being less effective. It is difficult to improve without knowing whether one’s efforts are moving one in the right direction or not.

(Note the ideas in this blog are explored in more detail in the chapter "Client feedback: an essential input to therapist reflection" in the forthcoming Haarhoff, B. and Thwaites, R. (2016) "Reflection in CBT: Increasing your effectiveness as a therapist, supervisor and trainer." London: SAGE Publications Ltd.)

Let’s imagine that I’m a darts player and I want to learn to get higher scores when I play. How would I feel if I went to a trainer who said something like "No problem; you need more practice. Here, let me put this blindfold on you so that you have no accurate idea where your darts are landing on the dartboard. Now practise away!" How many hours of throwing darts at an invisible dartboard would we need in order to become more effective? How many hours of training workshops and clinical practice do we need to improve when our outcomes are largely invisible to us? OK, we can maybe say with some accuracy whether a client has improved or not while we are seeing them. But is the improvement miraculously surprising or would they actually have improved faster if they had not been coming to psychotherapy and was any improvement achieved despite rather than because of our work together? We do not know. Very few therapists have any idea how helpful they are.

We are blindfolded darts players ignorantly hoping that continued practice will magically help us to achieve better results. It is no surprise that a meta-analysis on doctors found that increasing years of practice were typically associated with worse results (Choudhry, Fletcher, & Soumerai, 2005), and for psychotherapists there seems little if any association between experience and client outcomes (Baldwin & Imel, 2013). We don’t know where our darts are falling. In a study of 550 clients treated by 48 psychotherapists (22 licenced, 26 trainees), the therapists were told that previous research at the clinic involved had shown that about 8% of clients typically deteriorated during treatment. The therapists were asked to identify this group of clients. At the same time, the clients were monitored and their progress charted against a large database of previous client treatment progress charts. This ‘actuarial’ system accurately identified 36 of the 40 clients who did worse – a 90% detection rate. The therapists predicted that only 3 of the 550 clients would deteriorate and only 1 of these 3 was in the 40 who did in fact worsen – a 2.5% detection rate where even the solitary accurate prediction was made by a trainee therapist not one of the experienced practitioners (Hannan et al., 2005).

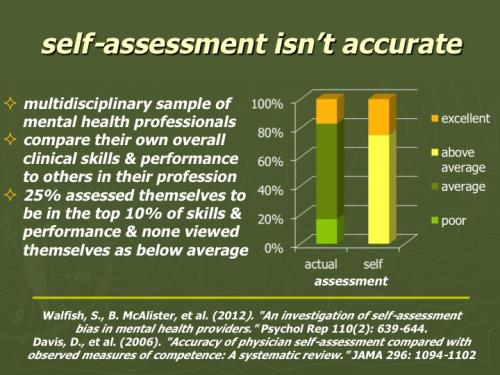

(This chart is downloadable as a Powerpoint slide or as a PDF file)

More recent research (Hatfield, McCullough, Frantz, & Krieger, 2010) has come to similar conclusions with the authors commenting "Therapists had considerable difficulty recognizing client deterioration, challenging the assumption that routine clinical judgment is sufficient’ and noting ‘Outcome assessment strategies do exist to help clinicians detect client deterioration."

So we have a situation in psychotherapy where 1.) The field as a whole has been painfully slow at producing better client outcomes. 2.) A lack of clear correlation between qualifications or experience and improved therapist effectiveness strongly suggests that our training methods need to be improved. 3.) There are however major differences between the effectiveness of different therapists. 4.) Identifying and studying more effective therapists looks like a useful research strategy that should be explored more fully. 5.) In parallel with this we can try harder to identify when we ourselves, as therapists, are being more or less effective – and then self-correct when necessary. 6.) Therapists seem to be bad at identifying when their clients are doing poorly – using routine outcome monitoring strategies to alert us to lack of client progress is very likely to outperform our surprisingly poor clinical judgement.

See tomorrow's post "Practice-based evidence can complement evidence-based practice so very well" for more on this.