Do psychotherapists, doctors and leaders develop "emotional chainmail"? Some ways of building both stability and empathy.

Last updated on 26th July 2015

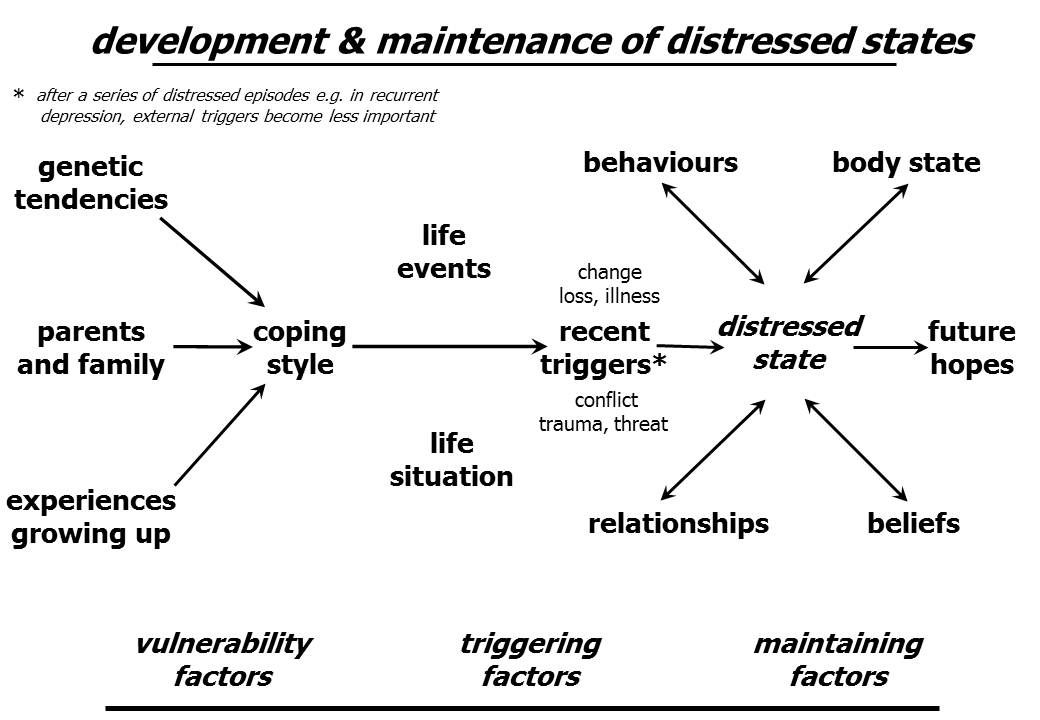

In the last couple of days I've written two posts on the possibility of developing "emotional chainmail" when faced with repeated experiences of suffering ... "Do psychotherapists, doctors and leaders develop "emotional chainmail"? Description of a possible problem" and "Do psychotherapists, doctors and leaders develop "emotional chainmail"? Two kinds of empathy". I have quoted research showing that being emotionally empathic to another's psychological or physical pain activates parallel pain areas in oneself, that medical training is frequently associated with reductions in empathy, and that a sense of power can lead to a deadening of sensitivity to the suffering of others. And this matters. Reductions in empathy strongly reduce how helpful we are for others. But how can we maintain or increase our levels of emotional empathy while maintaining our stability & resilience? In today's post I would like to suggest half a dozen ways of doing this. The diagram below is one that I use in explaining to clients why they have ended up in the distressed state that they're experiencing. However the sequence is also relevant to anyone's current state (including psychotherapists, doctors and leaders):

(this diagram is downloadable as a PDF file and as a Powerpoint slide)

One important factor relates to one's pre-existing level of psychological vulnerability. Attachment security in therapists, in leaders, and in pretty much anyone in a care-giving role (including those in couple relationships, teachers and, of course, parents) is associated with better outcomes for those we interact with - see for example the fascinating chapter by Mikulincer & Shaver entitled "Adult attachment and caregiving: Individual differences in providing a safe haven and secure base to others" in the fine multi-authored book "Moving beyond self-interest: Perspectives from evolutionary biology, neuroscience, and the social sciences". See too the papers "An attachment perspective on therapeutic processes and outcomes" and "Leaders as attachment figures: leaders' attachment orientations predict leadership-related mental representations and followers' performance and mental health". There's so much that's relevant here. This is a call to consider personal therapy for any psychotherapists (and others) with unfinished "attachment business" from their childhoods.

Significant life events and one's life situation in general are also relevant. If I was badly bullied as I grew up, or was assaulted, or involved in a severe car accident, or had other major traumas/life events and I haven't come to terms with what happened, I'm in danger of getting sucked into my own internal reactions rather than being empathically available for my client if they start to work on similar issues. Similarly and more broadly, if my client is working on issues about their job or relationship or self-care and I haven't addressed these issues in my own life, again there is likely to be unhelpful cross-over of distress. And as one would expect, this is relevant to other caring roles as well. See for example the 2012 paper "Linking peoples’ pursuit of eudaimonia and hedonia with characteristics of their parents: Parenting styles, verbally endorsed values, and role modeling" with its unsurprising but challenging finding that "people engaged in eudaimonic pursuits (seeking to use and develop the best in oneself) if their parents had either verbally endorsed eudaimonia or actually role modeled it by pursuing eudaimonia themselves. However, people derived well-being from eudaimonic pursuits only if their parents had role modeled eudaimonia, not if their parents had merely verbally endorsed it." There are parallel findings on leadership - see the post "The effects of leaders on organizations: a 'transformational', inspirational-caring style looks particularly effective". And more mundanely possibly, how well I look after my health as a therapist (how well I exercise, eat, manage alcohol, etc) will impinge on my stress levels and how effectively I can be present for the clients who come to see me.

These three strategies I've mentioned so far - therapists addressing their own unfinished business from childhood, challenging themselves to live autonomous, fulfilling lives in the present, and leading healthy lifestyles - are very likely to boost their stability & resilience. They may or may not boost empathy. On the whole, when we're less distressed and vulnerable, we're more likely to be able to care for others. But I've already mentioned the worrying finding that personal success can become associated with increased emotional distance from others - see Lammers & Stapel's recent publication "Power increases dehumanization". Happily it is very possible to consciously reverse this I'm-all-right-Jack tendency, as Cote & colleagues showed in their 2011 paper "Social power facilitates the effect of prosocial orientation on empathic accuracy." So power (as health professionals, as managers, as leaders, as teachers, as parents) increases our ability to cause benefit or harm to others. And here is my fourth suggestion for building both stability and empathy - consciously orientate ourselves towards doing good. One obvious and increasingly researched way of doing this is to practise some form of compassion meditation or prayer - see, for example, a couple of research studies published just last year - "Enhancing compassion: A randomized controlled trial of a compassion cultivation training program" & "Promoting altruism through meditation: An 8-week randomized controlled pilot study". And watch out for this kind of practice being associated with feelings of superiority - see the post "Personal experience: caution over "goodwill " & "mindfulness" practice". We're all in this together - we're born, we're likely at some stage to get sick, we lose those we love, we suffer, we die. Caring is for fellow travellers on this journey through life. I talked about this for myself in the post "Going back for a university reunion: stirring up memories, avoidant attachment, "puffing up" and kindness". As William Penn put it ""I expect to pass through life but once. If therefore, there be any kindness I can show, or any good thing I can do to any fellow being, let me do it now, and not defer or neglect it, as I shall not pass this way again." And mostly this is a win-win approach. There's a lot of truth in the Beatles' line "The love you take is equal to the love you make".

Fifthly, to encourage emotional empathy rather than just cognitive understanding, we need to engage & connect with the person we're empathising with. I'm fortunate and I tend to be very resilient emotionally. I regularly deliberately upset myself when I'm working with clients, taking their story and "stepping inside it" - imagining, for example, what I might feel if it was my wife who had left me, or my job I had lost, or my child who had died. And I can engage & connect as well with language & physical posture. Quietly mirroring words they use and positions they sit in is likely to be helpful if done with compassion & respect. This is a big research area that I hope to return to in the future. See, for example, the papers "Nonverbal synchrony in psychotherapy: Coordinated body movement reflects relationship quality and outcome", "Synchrony and the social tuning of compassion" and "Neural correlates of emotional synchrony." But as with power or skill in cognitive empathy, knowledge of the effects of imitative behaviour is double edged and can be abused or used in the service of compassion. The fact is that how we speak, our facial expressions, and the physical postures we take up will affect our relationships with others whether we want them to or not. We can do this unconsciously or we can learn something about these mechanisms and give ourselves more choice about the effects we produce.

My sixth and last suggestion here about nourishing empathy is for health professionals (and others) to get better feedback. See the series of three blog posts - "Compulsory multi-source feedback is coming or has already come to the health professions & to many other jobs as well", "Lessons from a personal multi-source feedback project" and "Some suggestions for giving and receiving helpful feedback". See too questionnaires available for throwing light on how one is doing as a partner in a couple or as a parent - "Relationships, families, couples & psychosexual". But more than getting overall feedback every once in a while from our clients, colleagues, partners & children I would underline the value of getting feedback in psychotherapy both on progress but also on the client's view of the therapeutic alliance every session - see "Psychotherapists & counsellors who don't monitor their outcomes are at risk of being both incompetent & potentially dangerous". I believe that the single most important change I have made in the last five years to increase the helpfulness of my work as a therapist has been monitoring the client's view of their progress and the session-by-session therapeutic alliance more carefully.