Personal experience (3rd post): feedback as opportunity & as a way of getting back on track

Last updated on 4th March 2012

In the last couple of days I have written posts on "Personal experience: feedback, group work & learning from difficulties" and "Personal experience: caution over "goodwill" & "mindfulness" practice". I'm a great fan of both mindfulness training and of using goodwill or loving-kindness or compassion focused meditation practices. However in the second of these two posts I raised one or two cautions about how effective mindfulness training is in promoting empathy and about possible "side effects" of out-of-balance goodwill practice. I ended the post by saying "What's much more over-whelming is the value of getting feedback."

The evidence for feedback's helpfulness in relationships comes primarily from one-to-one and couples psychotherapy. The post "Psychotherapists & counsellors who don't monitor their outcomes are at risk of being both incompetent & potentially dangerous" makes this point strongly and links to a whole series of other studies that have clearly demonstrated the value of regularly asking for feedback from clients both on progress and on the therapeutic alliance. I routinely do this. One of the four questions in the "Session rating scale", which assesses therapeutic alliance, asks clients to rate how much they felt "heard, understood, and respected" in the session. It's sensible to be suspicious that their responses may be slanted by knowing that I'm going to read & discuss their answers with them. However last year's conference poster presentation by Flora et al - "Social desirability and validity of clients' rating of the Session Rating Scale" - reported that "Monitoring treatment outcome and the therapeutic alliance has become a recommended practice. However, concern has been expressed that most client rate the alliance high. Clients (N = 173) at three sites were randomly assigned to three alliance feedback conditions to evaluate if social desirability and other demand characteristics influenced scores. Clients completed the Session Rating Scale (SRS; Miller, Duncan, & Johnson, 2000) the first three sessions of treatment in one of three feedback conditions: (1) Immediate Feedback (I) - SRS completed in presence of therapist and the results discussed immediately afterward; (2) Next Session Feedback (NS) - SRS completed alone and results discussed next session; or (3) No Feedback (NF) - SRS completed alone and results not available to therapist. No statistically significant differences in SRS scores across the feedback conditions were found, indicating that alliance scores are not inflated due to the presence of a therapist or knowing that the scores will be observed by the therapist. Additionally, the analysis showed that SRS scores were not correlated with a measure of social desirability but demonstrated evidence of concurrent validity with an established alliance measure." This is encouraging and underlines the potential value of using these kinds of assessment measures.

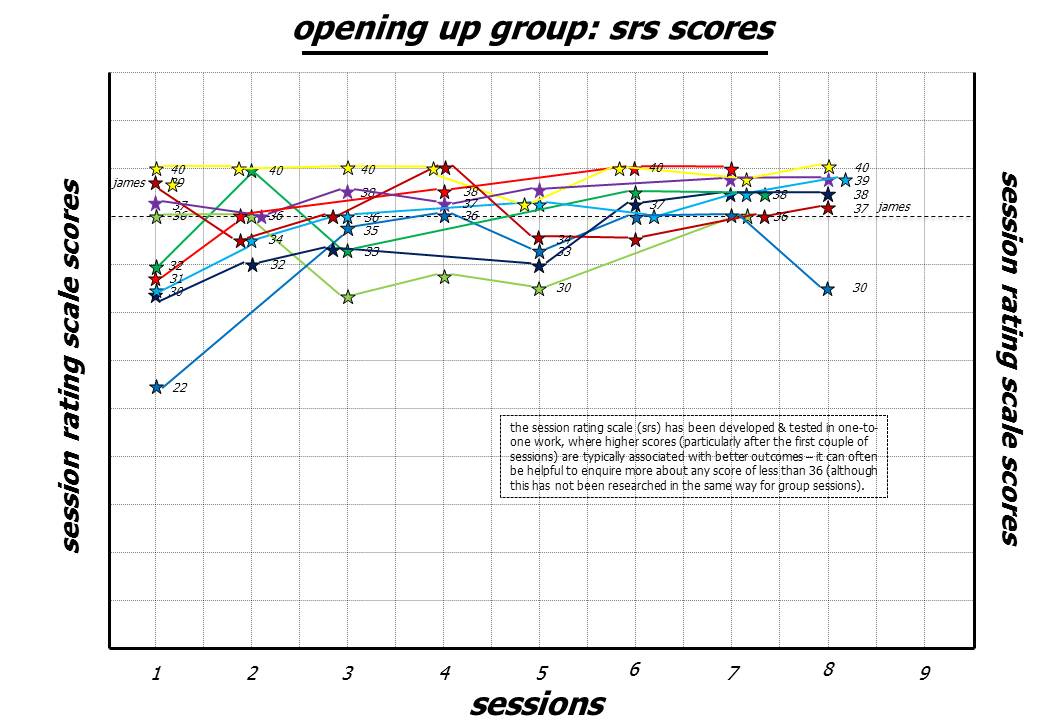

I've been experimenting with a slightly adapted SRS measure in a recent process group that I've been running (click here for a fuller description of these groups). All group members see everyone's SRS scores as they evolve week by week (including how I score the scale as well). Here's a copy of the chart for the first eight sessions of a recent group. I've taken out everyone's names except my own. Missing values reflect the fact that not all group members manage to get to all meetings and that, occasionally not all charts get filled in.

The four "Session rating scale (SRS)" questions that group members are answering on 0 to 10 scales assess the relationship, goals and tasks components of Horvath et al's working alliance (very slightly reworded to reflect a group rather than a one-to-one environment). All of us also complete a session reflection sheet. I scan these and send them out so that everyone gets to see both everyone's SRS scores and everyone's session reflection sheets before the start of the next meeting. Plenty of material for us all to chew over, but the SRS scores certainly help to guide what we do. Low SRS scores will be discussed at the next meeting so that people have a chance to voice doubts, dissatisfaction and confusion soon after they arise (as, for example, we did in the ninth session for the group member who scored themselves at 30 in the eighth meeting ... see chart above). Ideally one would catch these changing feelings in the session when they happen, but this isn't always feasible (there's so much going on in groups) ... so looking at them in the next session is usually very helpful. Additionally I've experimented with using this adapted SRS on a daily basis during a five day training workshop that I ran for fifteen health professionals. In this case I noted each day on a flip chart how many people were scoring in the range 36 to 40 and how many in the range 35 and below. I asked them to jot down a brief description of why, if they scored 8 or less on any of the four individual questions. This then generated daily discussion and seemed helpful in keeping us all engaged in the material we were covering.

Certainly in one-to-one work and in couples therapy, routinely collected formal feedback on the therapeutic alliance is associated with impressive reductions in drop-out rates and impressive improvements in the outcomes clients achieve. It's very likely that these benefits transfer, to a large extent, to the group environment as well ... but we still need the research to show this.

However, even the less formal feedback that one experiences regularly in interpersonal group work is potentially powerful and highly valued. I have been involved in a loose peer group network for over twenty years now. We typically meet for annual three or four day residentials. I've written about these meetings quite extensively in this blog - see, for example the description of a Scottish Mixed Group last October or of a UK Men's Group the year before. By no means everyone involved is a health professional, but some years ago I approached 46 colleagues who had been to these groups (45 replied). They were a mix of doctors, psychologists, counsellors, nurses, clergy and other therapists. I asked them "Please give a number somewhere between 0 and 10 to indicate approximately how helpful you feel these groups have been for you as a health professional, where 0 stands for 'not helpful at all' right up to 10 which stands for 'very helpful indeed'".

The average score came out as 8.4 ... a huge endorsement of the usefulness of this group work. Yes I know, the participant who scored their answer as "11" when given a "0 to 10" scale is a bit naughty, but that's what they said! For a fuller description of these findings in a broader talk, see the Powerpoint presentation I gave.

I'm not claiming that this kind of case series is any more than an indication that something interesting and helpful might be going on here. However, taken with the truly startling findings on the value of feedback in one-to-one & couples therapy, an intriguing picture begins to emerge. Intriguing enough for me to write the somewhat impish blog post "Is interpersonal group work better than sitting meditation for training mindfulness?" And certainly intriguing enough for me to be grateful for the feedback I received in our therapists' group at the weekend. An obvious extension, which I have already asked the other members for, is that they say if & when they feel I'm slipping into ways of caring that seem inauthentic to them during future group meetings. I might or might not agree with them! But it puts us all on the spot in a way that potentially involves real honesty, support & clarification for each other. Great ...